Lawyers use search algorithms on a daily or even hourly basis, but the way they work often remains mysterious. Users receive pages and pages of results from searches that ostensibly are based on some relevancy standard, seemingly guaranteeing that the most important results are all found. But that may not always be the case. This post explores the mystery of search algorithms from a legal research perspective. It examines what is wrong with algorithms being mysterious, explores our current knowledge of how they work, and makes recommendations for the future.

The Problem—Results Vary Across Algorithms

Upon the user entering a search term, each popular legal search database returns plenty of results. However, even with identical search terms, the result ranking may not be uniform or even close. Although researchers may rely on a particular database for their legal research and believe that the list of results is comprehensive, they may find otherwise upon closer inspection.

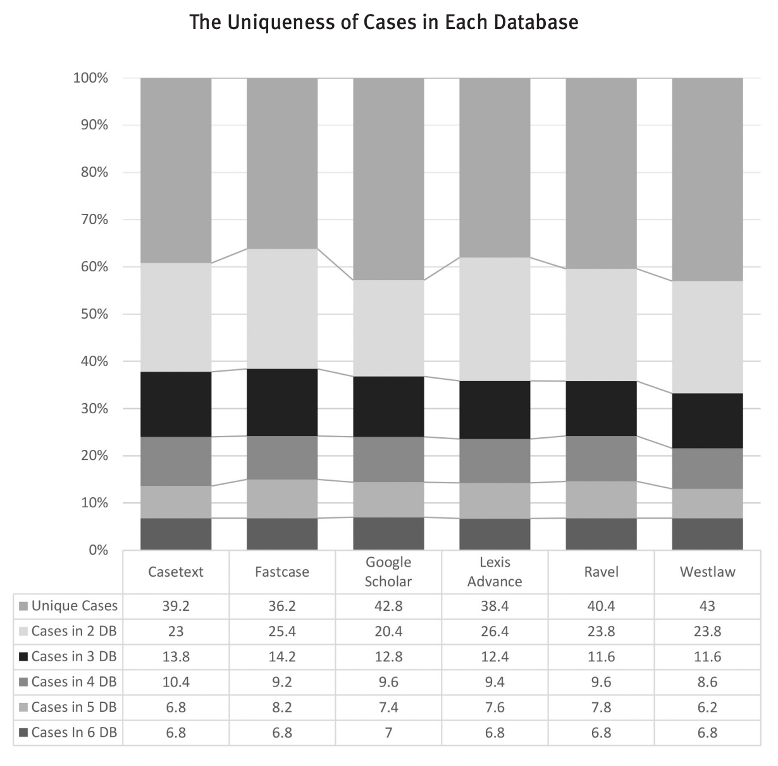

Susan Nevelow Mart, Professor Emeritus at Colorado Law, has spent significant time studying the phenomenon of search result divergence. She initially noticed it when she searched the same terms in different databases and received wide variations in results. To test this phenomenon, she ran experiments on a larger scale with fifty different searches and reviewed the top ten results. She focused on the top ten results because she understood that to be the focal point for internet users. Her experiment included six popular legal search databases: Casetext, Fastcase, Google Scholar, Lexis Advance, Ravel, and Westlaw. She assumed that the algorithm engineers behind each database had the same goal: “to translate the words describing legal concepts into relevant documents.”

Her findings show that every algorithm is different, as are their search results. She found an average of 40% of the top ten cases to be unique to each database. She also found that around 25% of the cases only appeared in two of the databases. This means that of the top ten cases from each database, four cases did not appear in any other database. Furthermore, if Lexis and Westlaw are compared alone, the results showed a striking 72% of unique cases. Although law students and attorneys likely consider more than the first ten results, practically speaking, that means users of one database might be looking through a dramatically different list of cases compared to users of a different database. This might lead to them citing and quoting different cases that the others may not have even seen.

Researchers from the University of Cincinnati employed an improved topic modeling analysis on cases from the Harvard Caselaw Access Project corpus to get at the same problem. Topic modeling is an algorithm that maps the statistical relationships among words. In searching for cases about “antitrust” and “market power,” researchers compared the visualizations based on topic modeling with results from Westlaw or Lexis. Curiously, the Westlaw or Lexis results showed classic cases in the field, while the visualizations showed cases that weren’t considered classics but were nonetheless influential in practitioner circles. There was a lack of overlap between them. This finding reveals that not only do algorithms produce differing results, but they may also miss essential cases that are often used in the real world.

Our Knowledge—Significantly Lacking

Once we recognize the problem of search results differing based on the search database, new questions arise. How much do we know and understand about these search algorithms? Do we comprehend why algorithms might produce drastically different results? Can we use this difference to our advantage in legal research? Might it cause harm to legal researchers unwittingly directed to different cases depending on the search algorithm they used?

The short answer to how much we know about legal search algorithms is simple: not much. Advanced legal technologies have been described as “an enigma” for most practitioners because they lack the understanding of how these technologies work.

One reason may be the legal researcher user experience. Researchers typically go through three steps in a search. First, researchers generate keywords or a question. Second, researchers type them into a search box. Last, results are shown immediately after clicking the search button. Databases hide the processes and calculations behind the scenes of how these results were selected and ordered. As Professor Mart mentioned, “[f]or the most part, these algorithms are black boxes—you can see the input and the output. What happens in the middle is unknown, and users have no idea how the results are generated.”

Another reason is that search algorithms are complex. Most legal researchers are not algorithm engineers, so they find it unintuitive to understand how search algorithms function. When tackling algorithmic literacy, researchers Dominique Garingan and Alison Jane Pickard considered using existing information, digital, and computer literacy frameworks to find the best structure for understanding algorithms. After considering multiple frameworks and failing to find one that encompasses algorithmic literacy, the authors suggested that algorithmic literacy in the legal field may be considered an extension of all three frameworks. The pure difficulty of deciding which framework to employ showcases how hard it is for outsiders to learn and understand algorithms.

That is not to say that we have no knowledge of the inner workings of popular legal search databases. We know some of the basic factors that search algorithms focus on. In searching case law documents, Westlaw relies on citations, key numbers, and treatment history, among other factors. Westlaw uses machine learning algorithms trained on legal content that include a diverse set of elements in its ranking. Its algorithm runs through more than sixty queries that “determine alternate terms that may apply to an issue, the legal documents most frequently cited for that issue, and authoritative analytical resources that discuss the issue.” Lexis Advance, in ranking its cases, considers a combination of term frequency and proximity in documents, case name recognition, “landmarkness” of the case, and content type-specific relevance weighting factors. Fastcase’s search uses sixteen different factors to rank search results, including keyword frequency in documents, proximity, citation counts, recency, the aggregate history of the search system, and others.

Though this information is a helpful start for users to understand search ranking, it doesn’t give researchers a particularly detailed description. Legal research databases themselves have provided little help in ensuring users have a basic understanding of search algorithms. Legal database providers tend to view their algorithms as trade secrets and only offer hints on the inner workings of their algorithms in promotional materials. Despite knowing the factors each algorithm may consider in its searches, it is unclear if there are other factors that the algorithms also consider, and what the weight is of each element in the search results.

Recommendations

The first and most important recommendation for legal researchers and practitioners is not to limit themselves to one search database. While it may be the easiest and most cost-efficient way to search, using only one database may cause the researcher to miss critical cases or fail to explore cases others will use. A 2018 survey of librarians, researchers, and professionals at high positions found that the majority of respondents relied on more than one information database when conducting searches. Most used Westlaw, Lexis, and Bloomberg Law, with a small minority also using FastCase. Using multiple databases ensures researchers do not miss important cases that practitioners in that particular field may be well-versed in.

Another recommendation is for law librarians, law schools, and even law firms to engage in further teaching about how to conduct research. Law librarians should continue to act as instructors, experts, knowledge curators, and technology consultants to clarify how search algorithms work, and how legal researchers can offset their known shortcomings.

Beyond the legal field, experts have called for greater algorithmic literacy and transparency more generally in the age of algorithms. Susan Etlinger, an industry analyst at Altimeter Group, stated that we should question how our data are presented and decisions are made just as we may question how our food or clothing are made. What assumptions are built into the algorithms? Were the algorithms sufficiently trained? Were the factors considered appropriate? These are all questions researchers should consider to better understand the algorithms they rely on. Answering these questions is especially important when each algorithm considers different factors and shows different results, even when practitioners in the particular field of study have, for example, a standardized list of cases they believe are the most important.

Fundamentally, legal research professors’ and librarians’ curricula should include information about the role of algorithms in legal research and warnings of the differing results that may come from different databases. They should emphasize that each search database uses a different algorithm so that researchers become aware of discrepancies between them. Algorithms may create the impression that their results are always the most relevant and that researchers need look no further. We know that is not always the case.

William Yao is a Library Innovation Lab research assistant and a student at Harvard Law School.

Sources

Felix B. Chang & Erin McCabe & James Lee, Modeling the Caselaw Access Project: Lessons For Market Power And The Antitrust-Regulation Balance, 22 Nev. L. J. 685 (2022). https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1883&context=nlj

Faculty FAQs, Lexis Advance, http://www.lexisnexis.com/documents/pdf/20111216091630_large.pdf

Dominique Garingan and Alison Jane Pickard. Artificial Intelligence in Legal Practice: Exploring Theoretical Frameworks for Algorithmic Literacy in the Legal Information Profession. Legal Information Management, 21(2), 97–117 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1472669621000190

Annalee Hickman, How to Teach Algorithms to Legal Research Students, 28 Persp. 73 (2020). https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/content/dam/ewp-m/documents/legal/en/pdf/other/perspectives/2020/fall/2020-fall-article-6.pdf

Susan Nevelow Mart, Every Algorithm Has a POV, AALL Spectrum, Sept.-Oct. 2017, at 40, available at http://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/723/.

Susan Nevelow Mart, Joe Breda, Ed Walters, Tito Sierra & Khalid Al-Kofahi, Inside the Black Box of Search Algorithms, AALL Spectrum, Nov.-Dec. 2019, at 10, available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/1238/.

Susan Nevelow Mart, Results May Vary, A.B.A. J., Mar. 2018, at 48, available at http://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/964/.

Susan Nevelow Mart, The Algorithm as a Human Artifact: Implications for Legal [Re]Search, 109 Law Libr. J. 387 (2017), available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/faculty-articles/755.

Lee Rainie & Janna Anderson, Code-Dependent: Pros and Cons of the Algorithm Age, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/02/08/code-dependent-pros-and-cons-of-the-algorithm-age/.

Robyn Rebollo, Search Algorithms In Legal Search, https://lac-group.com/blog/search-algorithms-legal-research/.

WestlawNext Quick Reference Guide, WestSearch, https://perma.cc/S8GV-R5SL